Final

Frontier, Landrover Owner Magazine

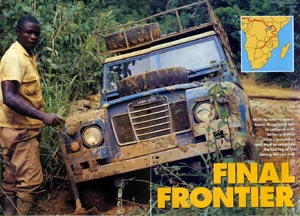

With

no time to spare, Kevin Muggleton has to contend with bribery,

police checks, punctures and mud to complete the last leg of his

daring African trek

Midway

through my trans-Africa route, I drove into Ghana with the Land

Rover shuddering violently over every pothole I hit - the steering

ball joints were shot. After 7000 miles on the road, many of them

so rough they could barely be recognised as tracks, the steering

had taken such a hammering it was inevitable something would give.

The carburettor was also continuing to cut the engine at low revs.

Shopping for parts in Accra provided all the new spares I needed

at very reasonable prices, and after only two days work the Land

Rover was back to its old self.

As I headed east, swallowing whole countries at a time - Ghana,

Togo and Benin - I vowed I wouldn't travel through Nigeria

after dark, and promised myself to avoid the capital Lagos at

all costs. But after I'd been questioned at the border for five

hours by the drug squad and the ugly secret police, and delayed

by 50 or more separate check points after the border, I ended

the day driving the streets of Lagos. The set for the film Blade

Runner must have been modelled on this city.

Above,

it could take up to five hours to dig the Land Rover out of holes

like this - even with local hired help. On the worst sections,

Kevin was managing to travel only 4km a day

There were burst water mains, flooded roads and, with no street

lights, vehicles crawling like leviathans through the dense diesel

fumes. Spotting my foreign plates, a gang in one car lurched across

my path but they were soon shifted as the Land Rover pushed them

off the road. In the most crime-ridden city in Africa, this was

no place to gamble on what their intentions might have been.

Lagos set the mood for the whole country and confirmed that Nigeria

had fallen into lawlessness. Motorists, harassed by the frequent

roadblocks, passed over handfuls of cash. Corruption was so rife

I was threatened with everything, from violence to imprisonment,

to convince me to hand over money. With ill-feeling, I stopped

to sleep and refuel, taking advantage of Africa's cheapest petrol

at 11 pence a litre. Finding the fuel was a different story, but

when I did, I filled every tank and jerrycan to capacity before

leaving the country.

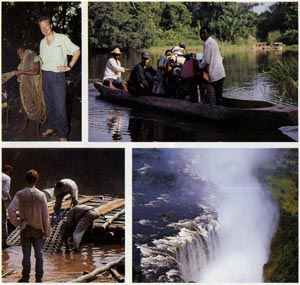

Clockwise

from top left, 6ft 3in author with the tallest of a Pygmy tribe

how to get a bike across a river; splendour of the Victoria Falls;

building a raft to carry the Land Rover

Driving through the Central African Republic and Cameroon, luck

was with me because I had missed the tail end of the rainy season

by just two weeks. Vehicles travelling during the rains make it

a costly business to repair the heavily damaged tracks, so officials

close rain barriers along the major routes to prevent any further

erosion.

The Ubangi River forms the border between the Central African

Republic and Zaire. Along the river, the lowland region is a mosquito-ridden,

steamy climate and it was here that I succumbed to my first bout

of malaria. I was racked with fever and vomiting. Treatment was

a simple course of prophylactics and antibiotics but afterwards

even the simple task of changing a wheel became a momentous chore.

To conserve energy for the heavy mud sections ahead, I cut the

driving days to about five hours.

The Amazon of Africa, Zaire has the second largest rainforest

in the world and is larger than western Europe. Accompanied by

a violent uprising, independence came in 1959 and since then there

has been no investment in communications or roads. Heavy annual

rains have meant that roads built during the colonial era have

been washed away. Politically, the country is a mess as President

Mobuto has developed a feudal system to dispel attempted coups.

Even finding an open border post is difficult. I wasted valuable

fuel on many detours searching for a crossing point that hadn't

been closed.

Finally it was far along the border at Bangassou that I found

a crossing point. To enter Zaire I initially took a pirogue (a

dugout canoe) across the river in search of the barge operator.

It was here I met some Belgian and Dutch travellers and together

we negotiated for two days with border officials before they eventually

let us through. Withnowhere else to cross, negotiations were a

slow process as I went through the finer tax charges. In hindsight,

the road tax was a scam, as I found nothing that could be classed

as a road.

The tracks in the drier northern Zaire were the least damaged

but you still needed your wits about you. Rivers crossed the tracks

repeatedly, and the makeshift bridges, made from fallen trees.

were precarious. It pays to take your time over these - I didn't

always and twice a wheel slipped off, leaving the Land Rover dangerously

perched on the edge.

Without warning, the new relay unit I had purchased in Ghana snapped.

There was no welding equipment anywhere nearby to repair it, but

luck favoured me because hidden nearby in anovergrown mission

was a non working Land Rover with the very part I needed. After

making a £40 donation to the local church I had; the old

part removed and was my way the same day.

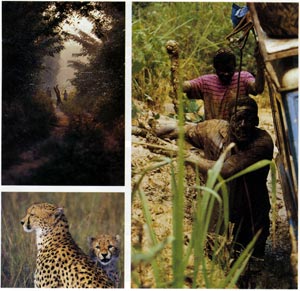

Clockwise

from-top, main forest tracks are busy with foot traffic during

the day on clearing a mud hole is like emptying a swimming pool

with a shovel; Cheetahs on the open plains

I predicted the route would deteriorate as I pushed further south

and I wasn't disappointed. The small ferry I had planned to cross

the Bili River on had been sunk by the drunken operator four months

earlier. With my new-found Continental friends, we begged and

borrowed oil drums, collected our spare inner tubes together and,

within two days, had built a raft strong enough to float us across

the slow-moving river. This was very much the pattern of things

to come.

Moving south through Isiro and Wamba, the route took me deep

into the rainforest. Here, even during the so-called dry season,

it rained daily and I entered the most appalling area I have ever

driven.

The Land Rover immediately plunged into a quagmire of reddish-brown,

wet, sticky clay. Three hours digging later and within minutes

I had driven headlong into another -there was no escape. The track

was walled in by rainforest, with no chance of a detour; the mature

trees were wider than the Land Rover was long. Friendly villagers

appeared and stared in amazement at seeing a white man for the

first time in ages. The mood quickly switched to astonishment

and then incredulity at my ludicrous form of transport. Here they

had long ago switched to bicycles, which are four times faster

than any motor vehicle.

Three weeks into Zaire and I was nowhere near where I needed to

be. At times I was hiring up to 25 Africans to help dig, shove

and cut a way through the rainforest. In hindsight, five more

shovels would have helped. Even walking through the potholes to

gauge the depth was no guarantee of success.

Although I was weighed down by a full fuel load, at least the

jerrycans could be unloaded: a huge benefit over using extra fixed

tanks. Driving was a test of nerves as, to avoid grounding the

diffs, I had to climb the wheels onto the central ridge at a precarious

angle. Driving like this for two kilometres at a time forced the

vehicle against the mud banks, chiselling the side, smashing the

lights and denting every inch of bodywork.

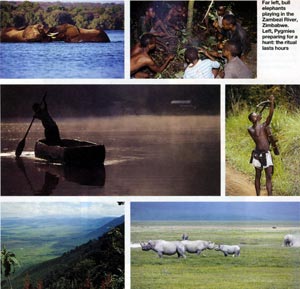

Centre

left dugout canoes cross the rivers from dawn to dusk. Above centre,

hunters live deep in the rainforest. a Above, wildlife in the

extinct Ngorongoro crater (left )

First

and reverse gears in low ratio were the only gears I used, pausing

for up to five hours to dig and scoop the vehicle from one hole

to the next. This routine continued daily for up to 12 hours.

Questioning how the route fared ahead proved futile as the villagers

had had no experience of driving. Some days I covered only four

kilometres, but on good days I managed over 20. At least the slow

pace allowed me to appreciate the surrounding kaleidoscope of

colours and some of the friendliest people I've ever met.

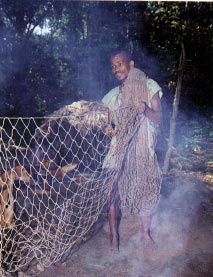

Left, readying the nets before a hunt. Left, readying the nets before a hunt.

The Pygmies I visited had spumed all attempts to integrate them

into modem life. Living a raw and primitive lifestyle, deep in

the rainforest, they used poisoned darts and spears to hunt and

built huts from leaves; they even used plants for medicine. Off

the beaten track, the Land Rover wasn't an option. The forest

was thick with primary and secondary growth trees, and I had a

brief glimpse into their lives.

After leaving the Pygmies 1 focused on driving out of the mess

and into Uganda. Four hours along the cratered track to Mambasa,

I found a Toyota Landcruiser stuck in the ruts and blocking the

route. With no room to turn around and use the heavy-duty military

towing hook, I wrapped the chain around my front bumper. As the

Toyota slowly lifted from the mud, my chassis broke above the

left wheel -but fortunately not all the way through. Then, while

avoiding holes as best I could, a branch smashed through the passenger

window and took the door clean off at the hinges.

I found a fully equipped Catholic , mission in Mambasa and the

priests set their apprentices at cleaning up the break and welding

a box section around the chassis. Again, an old Series III came

to the rescue as I relieved it of its door. The window was missing

so, for security, sheet steel plate was made to fit.

Below,

bicycles are quicker than any motor vehicle in Zaire. Below left,

it's easy to get lost in the forest where the Pygmies live.

The Land Rover was complaining by the time I hit the tar roads

of Uganda. It was in need of a major overhaul. With the thick,

caked mud washed off, the extent of damage caused through Zaire

was visible. Beneath the window line, bare, crumpled aluminium

was revealed, with little paint to speak of. The headlight surrounds

had caved in and the chassis, after repair, was sitting at an

uncomfortable angle. The clutch snatched, it was difficult to

engage low gears, the gearbox had a deafening whine and I donated

the mangled roof rack to my next host.

But I still needed to drive 4000 kilometers, via the Ngorongoro

crater in Tanzania, to reach Victoria Falls in southern Africa.

Driving through East Africa is usually a doddle, but driving it

with threadbare tyres was a nightmare. Police vehicle checkpoints

abounded and it took a swift tongue to talk my way past each point.

With the end of the trip in sight, the last thing I wanted to

invest in was another set of tyres.

Puncture stops frequented the long roads through Zambia. The police

rarely see a Land Rover in such poor condition and, in sympathy,

turned a blind eye. Three hundred kilometres north of Lusaka,

the back left tyre blew out -the tread had finally worn through.

The inner tubes on the remaining tyres were so badly punctured

that

Even the repairs were wearing out. Realising I wouldn't make it

the whole way, I bought a new tyre in the first town I reached

and was stung with a bill for £200.

Driving across the bridge between Zambia and Zimbabwe, the refreshing

spray of Victoria Falls soaked the vehicle and I still had a week

before my flight back to the UK. Twenty thousand miles and five

months after starting out, the Land Rover was a write-off by UK

standards. So I left the Landrover with a friend in Zimbabwe.

He has since replaced the tyres, beaten out the bodywork, rewelded

the chassis, overhauled the gearbox and has just returned from

a trouble-free adventure around Botswana and the Namib Desert...

My next major drive will be from Argentina to Alaska, and you

can count on me searching out one of Solihull's ageing finest

to stand up to the task.

|